Cave paintings

An amazing journey of a thousand years The enormous cultural richness of Guachipas is concentrated in the rupestrian paintings found in Las Juntas, so called because of the tangled junction of the rivers Las Abras and Las Pirguas.

Right in front of the square, the Interpretation Center is a good starting point, since to go on the tour without the expert's account would be a waste. There you can ask for Raúl “Pájaro” Aguirre, who guides the visitor through a magnificent journey into the past.

Already on the road, along the old National Route 9 (nowadays Provincial Route 6), Pájaro starts explaining the origin of the town's name: in the Cacán language "huachi" means "to shoot with arrows" and "pas" means "abundance of sunlight".

Then he narrates that in his first visit to the caves he felt that he had already been there in the past. His sensitivity towards the archaeological treasure is clearly perceived. It is a relationship of attachment that unites him to all the testimony of the culture there, in drawings so simple and - at the same time - so nourished with wisdom.

The 35-kilometer journey takes about an hour from the Interpretation Center. It involves going up the slopes of Cebilar and Lajar through the road to the old Pampa Grande farm, where the mules and cattle grazed and which was a fundamental enclave for feeding the troops of the Northern Army in the independence war. Decades ago, the historic Turismo Carretera, Argentina's most traditional motor racing competition, also used to pass along this path.

In the distance, to the east, the sacred hill of Las Pirguas can be glimpsed, reflecting the last rays of sunlight at sunset.

Once the detour is made, where a small sign indicates the arrival to the land of the legacy of the Diaguita-Calchaquí culture, the vehicle is left and a one-kilometer walk begins towards the caves. They are actually mountain overhangs, where precious drawings over a thousand years old have been found.

The Diaguita of the area were peaceful farmers, says Pájaro. He then argues that, according to his research, the Incas never came through these hills and, therefore, everything you see there is clearly pre-Inca. For him, it is not only a matter of studying archives and compiling the oral testimonies of the elders; one must also observe, hear, smell: everything on earth is "information", its stones, its plants, its streams, its sky. You just have to know how to take the time to decode it, he says.

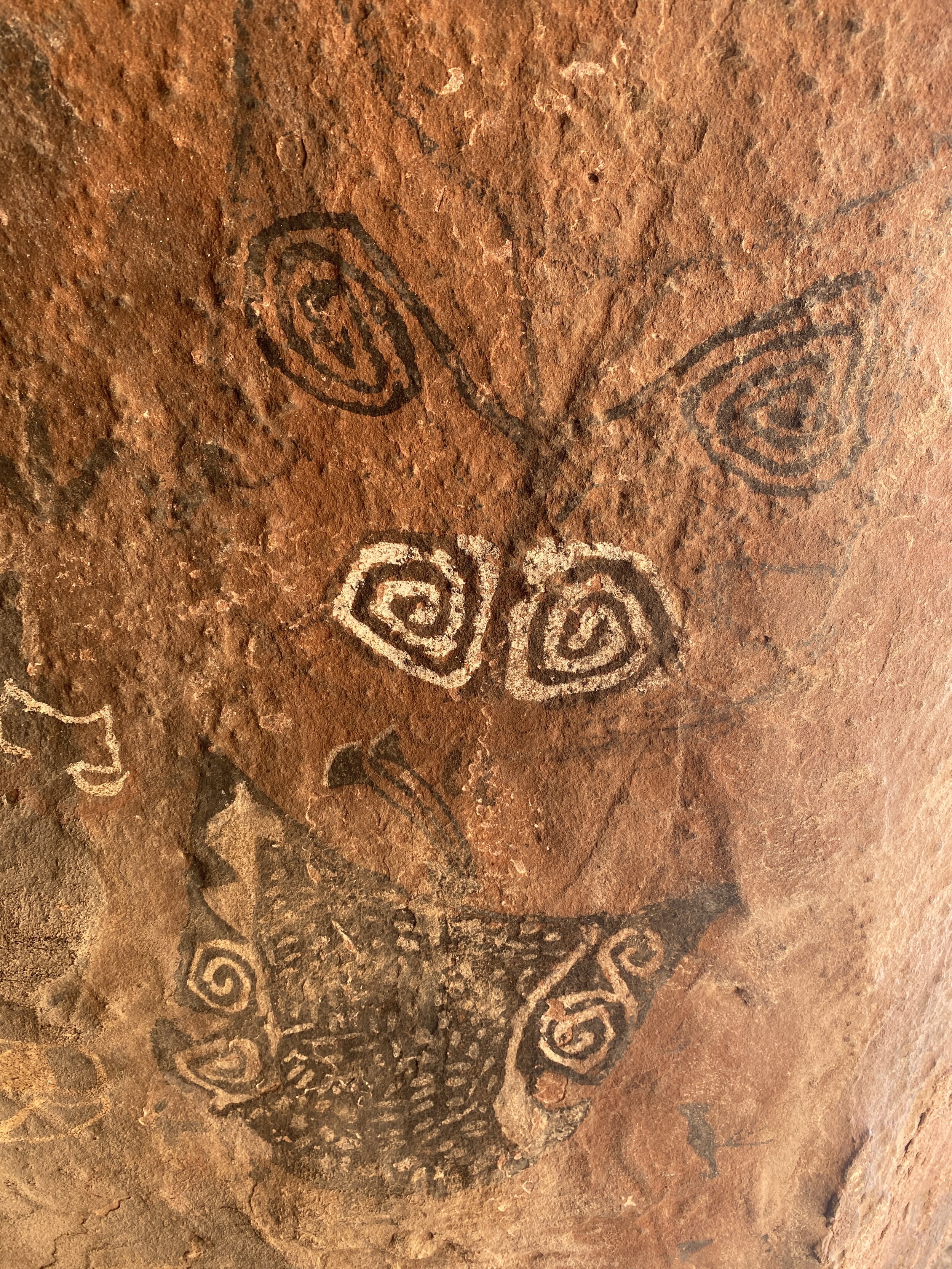

The eaves are made of pirgua, a geological formation of sand with reddish clay. In the first of them, baptized of the Initiation, it was customary to become an adult adolescent through a ceremony in which he had to cross a hollow of rock, with clear morphology of maternal womb. There are also paintings representing "counters" (a system in which each point is equivalent to a unit) and spirals, symbolizing the cycle of human life.

On one side are the first water mirrors, used by the Diaguita to absorb all the sun's energy concentrated there. These mirrors appear throughout the tour, the most important being the ones located at the highest altitude.

The methods of astronomical observation are astonishing. In this section there are seven tiny holes dug in the rocky path, which were filled with water. The night that all these holes reflected the light of the Seven Little Goats, the famous stars of the constellation Taurus, marked the beginning of the corn planting season. Impressive!

The adjoining overhang has a rock with a very particular shape: two semicircles that almost join, in the manner of the "intihuatana" of the Incas. When the sun appeared through that cavity, they predicted according to its light how the agricultural season would be: yellowish color meant a sunny and dry year; greenish, very suitable for sowing; mostly cloudy meant a year with calamities.

Continuing the ascent, Pájaro tells that the paints were made with natural pigments mixed with fox fat; for the black, charcoal ground with clay was used; for the red, the tannin of the cebil, which was concentrated in clay pots for a long time until the stability of the raw material was achieved; for the white, crushed limestone.

Pájaro invites you to lie down on the ground, almost entering a cave. It is in the eaves baptized Ambrosetti (after the ethnographer who studied them) where the two-dimensional and more colorful drawings are found. They are the "shield men" and the elders of the council, which form an absolute beauty. Simple figures but of vigorous workmanship.

Then, the eaves, which shows the life cycle of the animals. There, Pájaro stimulates the imagination, inviting to participate in guessing games or how one interprets what one sees, as in the case of the herd of llamas in a calm and relaxed attitude, which is evidenced by the festive posture of the offspring playing with each other.

Another higher eave contains a narration of an astral journey of the shaman. It is surprising to see the line that ascends to the sky through the rock in the height and even more surprising to imagine the artist executing it more than a thousand years ago, surely under the hallucinogenic effects of the cebil seed smoked in a pipe.

Already in the final phase of the ascent, after the eaves of the Senate, the stone of the sacrifices and an apacheta are found. By then Pájaro asks to open your arms and also absorb the energy of the sun and the place, confirming his intention to perceive the sensibility of the summit. And he succeeds!

Before heading back, a quick visit to the very old and shabby pink house that was the main town of Las Juntas, where my great-grandparents used to live.

An emotional ending after an amazing journey through time, full of pleasant sensations.